Most of this week has been taken up with organistion of a study day on Renaissance Cosmetics at the National Gallery of Scotland – more info at the Making Up the Renaissance website. It’s been a real pleasure as I’m co-organising it with Tricia Allerston from the National Galleries, one of my PhD students, Jackie Spicer, and Anna Canning, a herbalist and, luckily for us, all round polyglot wonder. Anna is making up some cosmetics recipes from Caterina Sforza’s Experimenti, a text that Jackie worked on for her masters dissertation last year, and we worked out yesterday which recipes we should try out. We plan to post Anna’s modern version of the recipes, plus photos of the result of us trying out these recipes on willing student volunteers, on the website.

There are lots of unanswered questions about renaissance cosmetics, which have not been studied very much to date, despite the fact that it’s a great subject for considering issues like female identity, ideas of beauty, the impact of disease on populations (many of the cosmetics recipes seem to be related to ridding the face of scarring due to skin disease), the availability and understanding of ingredients, early medicine in the home, and how health problems were tackled in the home.

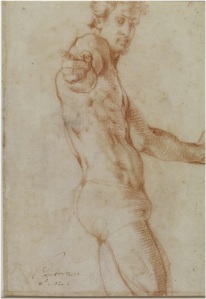

My own interest is through the work I’m doing on body image – in particular, I was trying to work out if pubic shaving was something that became more popular when images of hairless female nudes became more diffused in the early sixteenth century: did women try to make their bodies look like classical sculpture? Was the invention of the flat reflecting mirror towards the end of the fifteenth century responsible for people being more body conscious? One thing it did make possible was full body naked self-portraits, like the one by Pontormo to the left (this image taken from the fantastic British Museum collections database).

Trying to find out this kind of thing is difficult even now – but it’s really difficult if you’re peering through 500 years of history. One of the sources you can look at though are a type of book called Books of Secrets – lists of recipes for cosmetics, medicines, even sometimes poisons, that were designed to be made up at home. There’s several Italian books of secrets from the sixteenth century, and they all do seem to contain recipes for getting rid of body hair. The evidence would suggest that some women certainly did shave, or otherwise remove, their pubic and body hair during the renaissance, sometimes in rather terrifying ways. Here’s a recipe from a 1532 Book of Secrets:

how to remove or lose hair from anywhere on the body… boil together a solution of one pint of arsenic and 8th of a pint of quicklime. Go to a baths or a hot room and smear medicine over the area to be depilated. When the skin feels hot, wash quickly with hot water so the flesh doesn’t come off.

Not one we’re trying on the study day.

Leave a comment